Harassment behind the headlines: North East’s female journalists speak up about online abuse

Written by Godstime David on 16th October 2023

Female journalists in the North East of England have raised safety concerns linked to online abuse faced while fulfilling their roles.

Journalists in Middlesbrough, Darlington, and others in the area said the extent of online harassment experienced includes death threats, criticism of the quality of published work, and general safety concerns for friends and loved ones.

These concerns, they say, have significantly affected their approach to news reporting one way or the other.

Former journalist turned public relations officer, Naomi Corrigan, said while nothing bad ever happened as a younger reporter she admits to feeling anxious about certain letters she received.

However, she recalls brushing off these concerns, as they were considered a regular aspect of the job during that time. She also admits that things got worse when news went digital, and people could send messages via email, social media, and readers’ comments.

She said: “As I got older and, particularly after having children, I took threatening messages more seriously. I remember one of my colleagues was given a panic alarm that he could use if he was followed back from court, and I can remember feeling very uneasy about that. Fortunately, the attitude of management changed over the years, and we were encouraged to report any abuse which made me and my colleagues feel a little at ease.

“We would often see readers’ comments criticising our reporting or calling us names but that didn’t affect me too much as it’s quite a widespread issue on social media and in the comment sections on news websites in general. I would sometimes feel angry with an urge to respond to criticism but that would have only fanned the flames, so I did learn to ignore comments or avoid reading them entirely and just focus on my work.”

Ms. Corrigan added: “I would say the stories which attracted the most abuse were court stories. It was usually from the families of defendants or the defendants themselves, accusing reporters of telling lies or twisting stories, which is illegal and doesn’t happen. However, after the initial abuse following the publication of a court story, those issues tended to die down fairly quickly.”

A journalist in Middlesbrough who spoke on the condition of anonymity said: “About 10 years ago I had a huge pile of abuse from people due to a murder case I’d reported on involving well-known people. Comments such as ‘chase her out of town’ and ‘she needs sorting out’.”

“On another occasion, I covered a court case and the defendants set up a Facebook page titled ‘you are a b***h’. I remember at the time feeling very stressed and anxious and scared for me and my family’s safety.”

She said that her current position doesn’t necessitate extensive personal engagement on social media platforms. However, it does involve sharing reporters’ stories. She noted that if the team foresees a potential for abusive comments on a particular story, they opt to disable the comments section for that article and extend the action to all social media platforms.

“Occasionally, I do write stories, and get odd comments saying ‘slow news day’ or trolls trashing what we/I have done. I tend to let that go over my head. It’s when you think it could affect yours or your family’s safety that it impacts me more.”

“But in dealing with reporters, if it’s low-level name-calling or calling into question their talent/work, then I reassure them that these people are just keyboard warriors. If it is something more serious, like a threat to safety, then we flag this to our online safety team, management, and the police if necessary.”

Kayleigh Fraser, a reporter at the Northern Echo, said her career journey has been quite interesting. She highlighted that, like any profession, there are both good and challenging days, and receiving some form of criticism is part of the job, with most instances revolving around minor issues. These could include differing opinions on a review or pointing out small, inconsequential errors.

“One example I have is when I did a story about a man who was complaining about traffic build-up. The man sent me a photo he took when he was behind the wheel and clearly at a stop. One guy found it and put it on Twitter, tagged me in it and everyone started throwing hate my way. I had to mute the app.”

“If you post on crime, it’s too negative, if you post on a funny story it’s not proper news, if you focus on something really hard-hitting – nobody reads it. The abuse sometimes makes me want to hermit and not even look at the comments. But we are told not to look at the comments as they can affect us in different ways and it’s a dangerous game to play when you don’t know if it’ll be positive or negative.”

She added: “In other cases, it’s not just commenters that give abuse – it’s sources.”

“You’ll have people who come to you and things can get very dark very quickly. They tell you things that are quite vivid and sometimes these things are really hard to move on from. Political stories get a lot of abuse but are usually not directed towards me.”

“The ones that get the most hate are digitally oriented pieces that people say ‘isn’t news’ but they get tons of clicks so it’s worth it to us. I try not to look at the comments or search for anything that would give me hate. If I do that, I keep my conscience clear.”

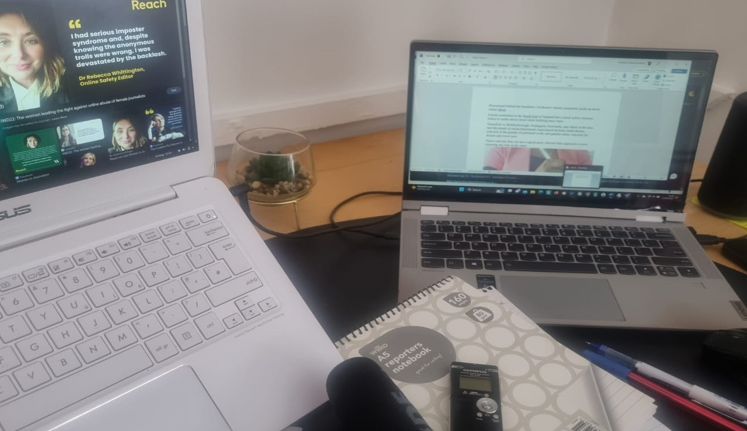

Dr. Rebecca Whittington, Online Safety Editor at Reach PLC, who led research on the online abuse of female journalists in the UK, noted that online safety has become a global challenge for women in journalism.

In the UK, a survey of over 400 female journalists found that 20% of them are thinking about quitting their jobs due to online harassment.

The study also found that some Journalists now see online abuse as part of the job or are told that it’s part of the job. “No one should ever accept abuse as part of the job,” she said.

“20% is a huge number which will be a real disaster for the industry if they actually leave. As an industry, Journalism needs to recognise the actual issue, put a structure in place that can support journalists reporting at war zones, contentious issues, or certain types of roles, and act in the same way a physical risk assessment is carried out for police officers and mental health workers.”

“Employers also need to recognise the issue and start finding solutions to it. When there is a complaint of online abuse, it should be taken seriously. Otherwise, people might be leaving the industry due to the lack of support.”

According to Dr. Whittongton, the impact on journalism includes Journalists moving away from frontline roles to behind-the-scenes, mental health issues, and the fear of the unknown or being attacked. She added that if they don’t have the necessary support to manage the situation, the mental health impact could be quite significant.

She added: “The police and a few news organisations are increasingly recognising this as an issue and are liaising with industry representatives to curtail it.”

“I do think a lot of work is being done, but it takes time. Ultimately, journalism is the most amazing, exciting career that gives you an opportunity to meet different people and travel the world. Never let the issue of abuse stop anyone from pursuing a career in Journalism.”

A spokesperson for the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) said: “The NUJ has done a huge amount of work in supporting women journalists against online abuse and raising awareness of the issue. We have commissioned a number of videos.”

“The union has also launched a mini-app safety toolkit with lots of information and advice, including how women can protect themselves from online abuse and report the perpetrators. We provide practical guides in combatting online harassment and abuse – a legal guide for journalists in England and Wales.”

The spokesperson said NUJ runs events such as combating online abuse and physical threats against journalists and uses the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to promote resources to help women.